80th Anniversary of The Battle of Bamber Bridge

‹ Return to Britain at War

The Battle of Bamber Bridge

24 – 25 June 2023 will be the 80th anniversary of ‘The Battle of Bamber Bridge.’ The events seem well remembered locally, and there are web pages about the incident but it’s something I only recently heard of.

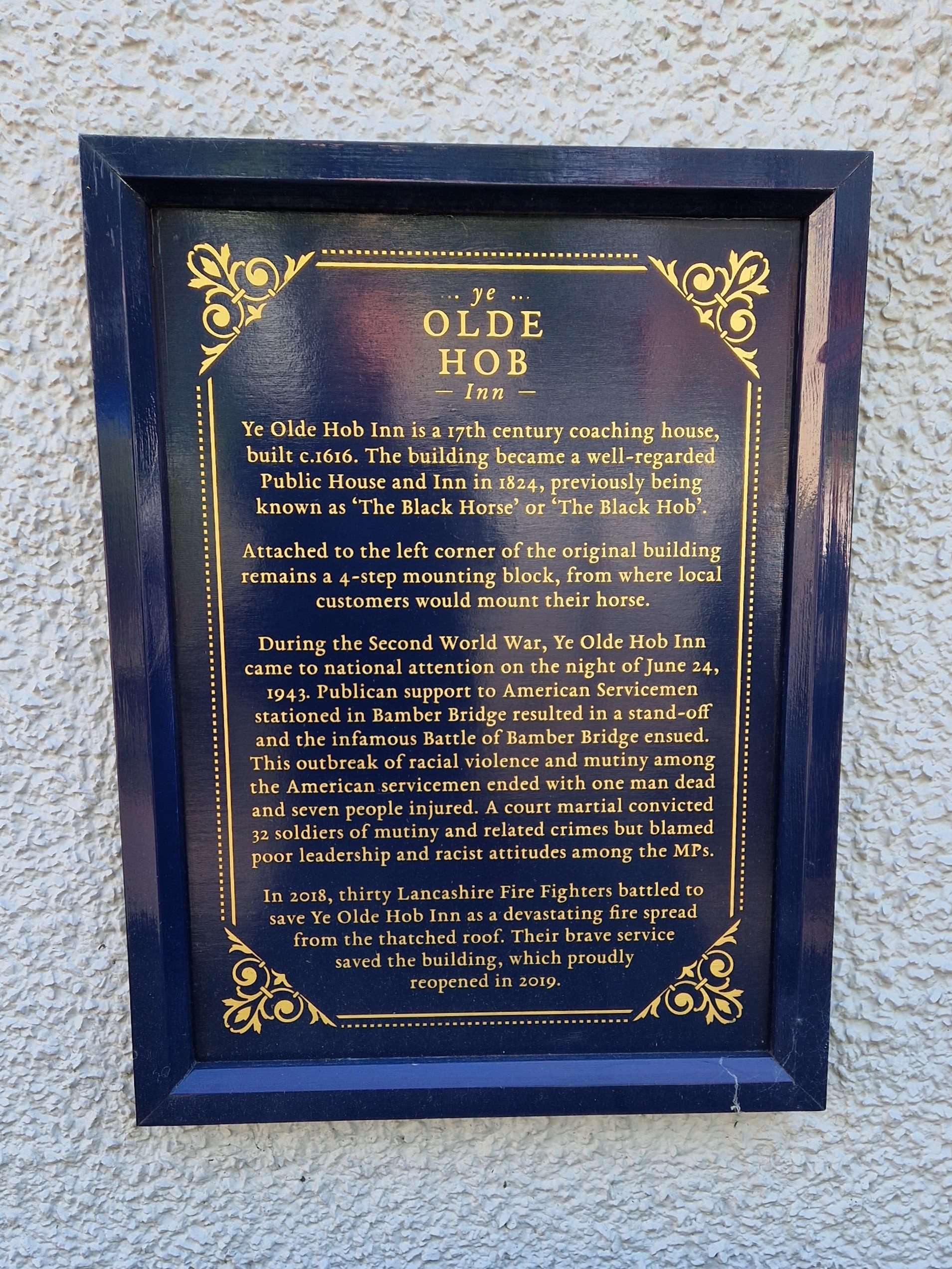

The lead photo above shows Ye Olde Hob Inn at Bamber Bridge, Lancashire.

American segregation in Britain

It is important to put this story in historical context: just two days before the events described here, the Detroit riots had ended, resulting in the deaths of nine white people and twenty five African Americans, with nearly seven hundred people injured (75% of those were African American) in the space of three days. No white people were killed by the police, but seventeen of the dead black people were killed by the police.

The riots in Detroit were the result of building tensions with overcrowding in cities and black people generally treated as second class citizens with the so-called ‘Jim Crow’ laws enforcing segregation. When African Americans moved into the city to work (Detroit of course providing many vehicles for the war, the demand for motors was never higher) they could not buy property and were forced to live in sub-standard accommodation. When black workers were promoted, white workers went on strike.

By June 1943, 19 months after the USA declared war on Japan and Germany, thousands of US servicemen – of which some 10% were black – were in Britain. Ambrose puts the figure at 150,000 black American soldiers in the UK by March 1944.

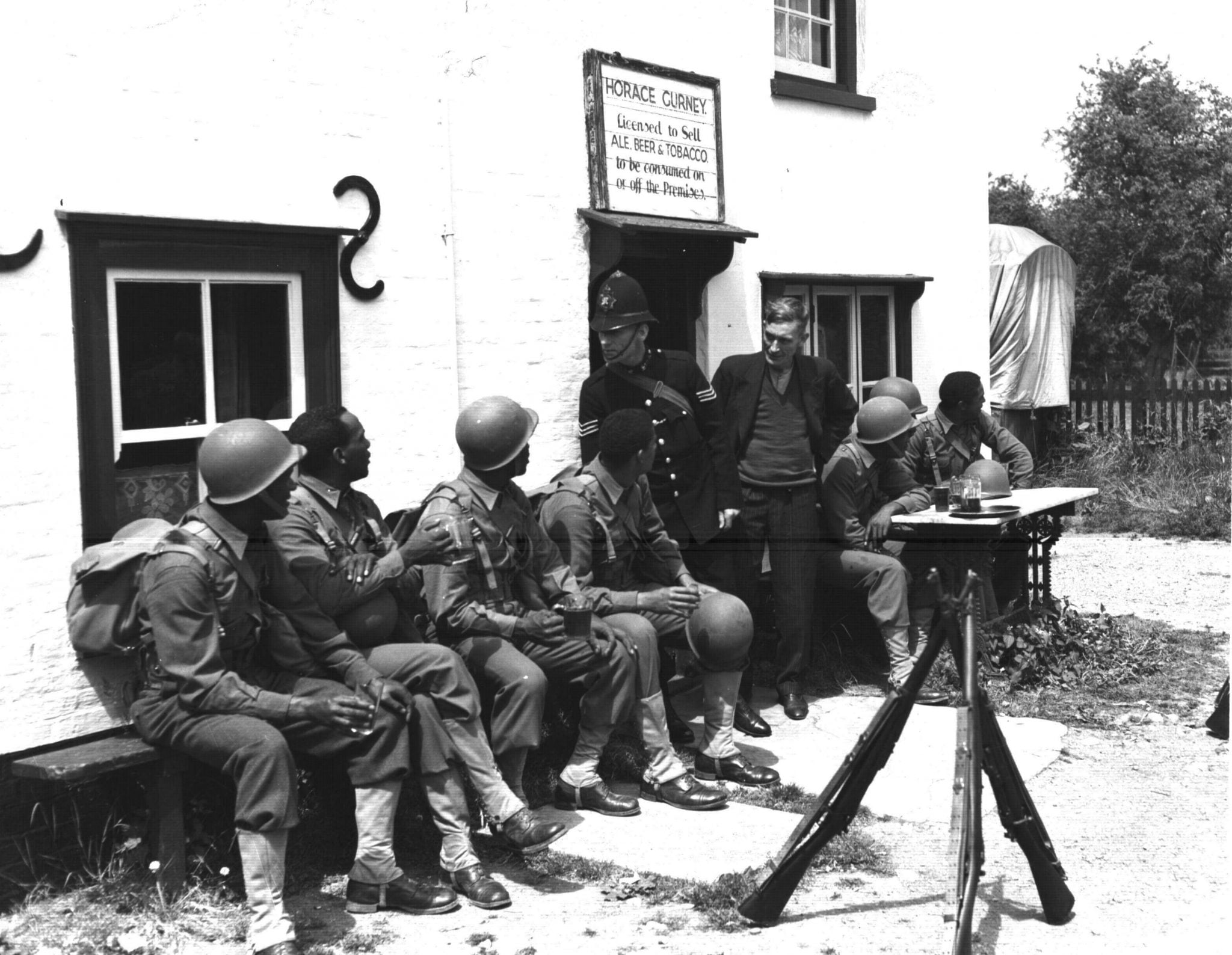

Photo: Imperial War Museum

American historian, Stephen E Ambrose wrote: “Racism was at the heart of Nazi philosophy. Racism was also present in the American army.”

Bringing segregation to Britain also brought conflict to Britain. In some places, attempts were made to minimise tensions by having a rota system keeping white and black servicemen apart. For example, the town of Tewkesbury had white troops having a pass into town on alternate days, while in other places, attempts were made to have a ‘black’ pub and a ‘white’ pub.

(Note I have seen this photo reproduced elsewhere with the caption being it’s the Olde Hob Inn at Bamber Bridge, but clearly it isn’t. It’s The Three Horseshoes near Hemel Hempstead with the landlord Horace Gurney and PC Lord, the local bobby)

But often, such attempts did not work for lots of reasons, the welcoming nature of Britons to black servicemen among them. While segregation in the USA meant black people could not use white only establishments, there was none of that in the UK. African American servicemen not only were able to drink in pubs and meet white British girls at dances, they were also very well received by the public. George Orwell was among many expressing the sentiment common in Britain, that black servicemen were “…the only American soldiers with decent manners.”

As for the fighting which often happened, Ambrose states that Major General Eaker, Commander of the Eighth Air Force, “declared that white troops were responsible for 90% of the trouble.”

Gardiner wrote “…a Birmingham man reported “I have personally seen the American troops kick – and I mean kick – coloured soldiers off the pavements…”

Bourne writes of an occasion where a West Indian airman serving with the RAF was assaulted by an American airman in a canteen: “…seeing the coloured airman quietly sitting at a table, strolled up to him and slashed [slapped] him across the face!” Everyone jumped up, expecting a fight. “A schoolmistress who was helping at the back dashed out and slashed [slapped] the American’s face, and her language was very choice! Anyway, they smuggled him out but our men said if they saw him again they’d kill him… Meanwhile the coloured man sat there as if dazed, it was so unexpected, so unwarranted. It seems amazing that the Americans are fighting on our side, when you hear things like that.”

White women were also at an unusual risk of being blacklisted by white soldiers and airmen at dances if they had been seen dancing with black men, and some pub landlords reported being boycotted by white American servicemen if they served black troops.

Of course, this wasn’t the attitude of every single white American in Britain during the war. Although the policy was one of segregation, the racism on an individual level as mentioned above was not always the case. As much is said by Evelyn Johnson in the video below and is evident in lots of accounts. But it was policy to discriminate.

24 June 1944 – ‘Battle of Bamber Bridge’

So, the US Army maintained the same segregation within their units as at home, thus the 1511th Quartermaster Truck Regiment, based at Adams Hall camp at Bamber Bridge, Lancashire, was made up of black GIs but with white officers (there was one black officer). The Military Police (MPs) were white, though attempts were made later to have mixed patrols. Also based in Bamber Bridge was the 234th Military Police Company.

At Bamber Bridge, there was an attempt by the US Army to make the pubs in the town out of bounds to black servicemen, just before the incident of 24 June 1943 according to Anthony Burgess. In his biography (he was a teacher at Bamber Bridge after the war) he wrote of how the US Army had asked the local pub landlords to ban black GIs. The response was the pub landlords put up notices saying “Black Troops Only.” However, this tale has not been verified. But as will be seen further in this piece, clashes with MPs were not uncommon.

That night then, some black GIs had been drinking in a pub in town called Ye Old Hob Inn. Having been hailed by three white American soldiers who told them about the black GIs still in the pub and not in their proper uniforms, two MPs, Corporal Roy Windsor and Private First Class Ralph Ridgeway, approached the pub at 10pm.

One of the patrol entered the pub and tried to arrest Private Eugene Nunn, on the grounds that he had not the correct pass and was improperly dressed, he was wearing a field coat apparently and not his Class A uniform. The MP asked him to step outside. The GIs – and the locals and some British service men and women from the pub – stood up to the MPs and refused to be cowed by them.

At this point in addition to the crowd of Brits, there were at least a dozen black GIs, all outside the pub and arguing with the MPs, the British especially telling them to leave the GIs alone. A gun was pulled by one of the MPs, but they backed off. As they left in their Jeep, a bottle was hurled at them, hitting the windscreen and bursting, showering them with beer. This was probably the tipping point for the Military Police which caused events to tumble towards tragedy.

The soldiers made their way back to their camp, walking along Station Road, probably a bit drunk and happy to have got the better of the MPs. Meanwhile the MPs, no doubt angry and humiliated, picked up two other MPs and went back to look for the GIs. They soon found them and a fight ensued in Station Road. One MP was hit over the head with a bottle, but three shots were fired, each injuring a GI. The MPs left the scene to find reinforcements while the GIs, carrying their wounded pals, got back to their camp on Mounsey Road.

Below: The riot began here on Station Road

That was the riot. What followed was the battle – or mutiny depending on the perspective of the people in the thick of it.

Upon returning to the camp, word quickly spread that the MPs were going to come back and murder them all (bearing in mind, this was just days after Detroit). Up to 200 soldiers were milling around, some already deciding to grab some weapons and find the MPs before they found them. The commanding officer – Major George Heris – attempted to restore order but was ignored. The one black officer in the unit, Second Lieutenant Edwin Jones, had more success and most of the soldiers began to calm a little.

However at around midnight a dozen MPs arrived in Jeeps and in a makeshift armoured vehicle with a machine gun clearly visible. As Werrell put it, “The rumour was true: white MPs were going to kill the black soldiers.” Some even believed the MPs were arriving in tanks.

Soldiers in the camp broke out guns and fired upon the MPs while at the same time, the sound of gunshot was heard coming from the town. Some GIs burst out of the camp in trucks, carrying rifles and headed into Bamber Bridge.

Below: Adams Hall Camp then and now. There is just one building remaining in 2023

One MP, having driven from Preston in his Dodge truck, was shot as he approached Mounsey Road, his vehicle taking 16 hits. He was lucky to survive. But Private William Crossland was less lucky. While standing at the corner of Cooperative Street and Station Road, he was shot in the back and died. It is possible it was a stray bullet which hit him and not an aimed shot bearing in mind Britain had a blackout, so there was no street lighting or lights from the houses all around.

Below: Where Private Crossland was killed

Below: Private Crossland’s grave, image from Find-a-Grave

The death of Private Crossland seemed to bring the fighting to a shocked close. Later that summer, thirty two GIs were tried and convicted for rioting and mutiny. There was some mitigation noting the absence of leadership but nothing about the racial discrimination which led to the fighting in the first place, and apparently, no mention at all of Private Crossland.

Below: board at Ye Olde Hob Inn and the memorial across the road from the pub.

Beyond Bamber Bridge

Confrontations between MPs and black GIs seemed common enough but the picture is not as straight-forward as white MPs versus black GIs. In one terrible incident on 05 October 1944, and reminiscent of the events at Bamber Bridge, three people were killed in the village of Kingsclere in Hampshire.

10 soldiers from a US Army engineering unit had been ordered back to base from the village pub, the Crown Inn, by MPs because they did not have a pass to leave base. The men did as ordered, but broke out some guns and returned looking to get revenge on the MPs.

One of the MPs, Private Jacob Anderson was shot dead outside the pub: he managed to get a hundred and fifty yards up the road but collapsed in a garden in North Street and “died between two beanpoles” (see Kingsclere Heritage Association, link below). The other military policeman, a Private Brown, dived back inside the pub and survived.

However, in the gunfire which followed as the mob shot at him, Private Joseph Coates – who was sat in the pub with his back to a window – was killed instantly when hit in the back of the head by a rifle bullet. He is listed as having “died in the ‘Line of Duty’ in a Non-Battle related incident during the war.”

The third person to die was 64 year old Mrs Rose Napper, the wife of the pub landlord, Mr Frank Napper. When the bullets started flying, he had dragged his wife to the floor, but a bullet ricocheted and hit her in the cheek, passed through her tongue and out of her neck, killing her.

All of the servicemen in this incident were black; the two MPs, one of whom was killed, Private Coates who was minding his own business having a pint in the pub and all those who killed them and Mrs Napper. I mention it here because I have seen this incident referred to as another between black GIs and white MPs, which is not true.

But there were other incidents where racial discrimination was the cause of conflict. In Launceston, Cornwall, at 10.20pm on 26 September 1943, a large group of black GIs from 581st Ordnance Ammunition Company made their way from their camp at Pennygillam to the centre of the village. There they confronted a group of nine white MPs in the town Square, demanding to know why they were not allowed into the town and its pubs. As at Bamber Bridge a few months earlier, the locals had stood up for the GIs against the MPs.

There wasn’t much of an argument before the GIs started shooting at the MPs. Two were wounded, but 14 of the black GIs were charged with mutiny and attempted murder and sentenced to death or life imprisonment.

Another incident was at Bristol, 15 July 1944, an incident known as the ‘Park Street Riot’ which involved an 400 black GIs (with some local white women among them) fighting with over 120 white MPs which ended with one MP being wounded and a black GI being shot dead. Another occurred in Antrim, Northern Ireland in September 1942, resulting in the death of a black GI and the wounding of a white GI.

A colour bar in Britain?

While there are numerous reports of black people being welcomed and being “treated royally” (see video interview below) and amazed at the absence of any colour bar, it would be wrong to say there was no racism in Britain at the time. Of course, there were individuals who then – as now – were prejudiced against people because of the colour of their skin but prior to WW2 there was a subtle colour bar in the British services.

Between the wars, the UK stopped recruiting non-whites into the forces. The law had to be changed out of necessity when war broke out in 1939. Nonetheless, Bourne says, “A Foreign Office memo dispatched to colonial governors stated, ‘We must keep up the fiction of there being no colour bar. Only those with special qualifications are likely to be accepted.”

Bourne tells the story of Lilian Bailey of Liverpool whose father was from Barbados. Upon the outbreak of war, she took a job with the NAAFI, at Catterick. However, the authorities in London became aware and she was sacked. Lilian said that at the time, there was a lot of fear of anyone foreign looking but felt “…. embarrassed when a group of soldiers at a gun post expressed surprise that she was not doing war work. ‘How could I tell them that a coloured Briton was not acceptable, even in the humble NAAFI?”

80 years on and attitudes have changed, for better or for worse. When a person of colour is shown in a WW1 or WW2 movie or TV drama now, a vocal minority will predictably comment that it’s ‘blackwashing,’ that black people (or those from south Asia) did not serve in WW2, when of course they did. And then there will also be those handful of people who will point out the absence of people of colour, such as in the 2017 movie Dunkirk: there are no black or brown soldiers in that movie, yet there were hundreds of North African French soldiers on the beach that week in 1940. And the British had the Royal Indian Army Service Corps on the beach at Dunkirk, one of whom was awarded the DSM for courage under fire. But you’d never know.

When I told my friend about the story of the Battle of Bamber Bridge, the first thing he said is “Why hasn’t anyone made a movie about it!” I don’t know why, but then as I said at the beginning, until a few weeks ago, I had never heard of it either.

(NB. I have seen 2022 film The Railway Children Return which has elements of the incidents described above but it’s not the story of the Battle of Bamber Bridge, as some suggest)

References and sources of information

Accounts vary, so I have tried to verify as much as possible using different sources and pointing out where there is only one source. Even then, a quote from one website or book is copied to another and it can become a ‘fact’, so it is likely there will be some details provided above which are not correct, though equally they may now never be proven one way or the other.

Also I have seen various photos, in print and online, purporting to show the men of the 1511th awaiting trial, for example, but they are false representations. I have seen the same photos produced elsewhere with different captions. I have not seen any photos which can be verified as being of GIs in Bamber Bridge.

The photos of Bamber Bridge are mine apart from the image from Find-a-grave. The mono photos are from various sources, widely available online – please see the links below for more. The photo of the GIs outside a pub again is widely available online, but the information identifying the pub is from the pdf referred to below.

Print

Ambrose, S.E., D-Day – June 6 1944 The Battle for the Normandy Beaches, 1994

Bourne, S., Under Fire – Black Britain in Wartime 1939 – 1945, 2020

Gardiner, J., Wartime Britain 1939-1945, 2004

Rogerson, D., The Battle of Bamber Bridge – The true story, 2022

Werrell, P., Mutiny at Army Air Station 569: Bamber Bridge, England, June 1943, published in ‘Aerospace Historian,’ December 1975. That article was updated and published in ‘After the Battle’ magazine in the UK in 1978.

Websites

Bamber Bridge Bulletin This page has an interesting account of how the memorial came to be, including how local ideas for the memorial were rejected. I agree with the author of the page. The page also provides details of events in the village to mark the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Bamber Bridge.

Preston Black History Group – the Battle of Bamber Bridge

Kingsclere Heritage Association

International Black History Month UK

BBC WW2 People’s War – Battle of Bamber Bridge

American Air Museum in Britain

Black Past – The Riot of Bamber Bridge

The personal diary of John Young Pdf

Short video of an interview of an American WW2 veteran about how she was treated ‘royally’ by British people. (Image shows Evelyn as she was then)

Image Information

-

Full Size: 2560×1920px

Aperture: f/1.8

Focal Length: 5.4mm

ISO: 50

Shutter: 1/940 sec

Camera: SM-S901B

Leave a Reply